Dvaravati

7th to 11th-century Mon kingdom

.mw-parser-output .hatnote{font-style:italic}.mw-parser-output div.hatnote{padding-left:1.6em;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .hatnote i{font-style:normal}.mw-parser-output .hatnote+link+.hatnote{margin-top:-0.5em}@media print{body.ns-0 .mw-parser-output .hatnote{display:none!important}}

Dvaravati (Thai: ทวารวดี) was a group of medieval Mon political principalities from the 6th century to the 11th century, located in the region now known as central Thailand,[5][6]: 234 and was speculated to be a succeeding state of Lang-chia or Lang-ya-hsiu (หลังยะสิ่ว).[7]: 268–270, 281 It was described by Chinese pilgrims in the middle of the 7th century as a Buddhist kingdom named To-lo-po-ti situated to the west of Isanapura (Cambodia), east of Sri Ksetra (Burma),[8]: 76 [9]: 37 and adjoined Pan Pan to the South.[7]: 267, 269 Its northern border met Jiā Luó Shě Fú (迦逻舍佛), which is identified with Canasapura in modern northeast Thailand.[10] Dvaravati sent the first embassy to the Chinese court around 605–616,[7]: 264 and then in 756.[11]

.mw-parser-output .infobox-subbox{padding:0;border:none;margin:-3px;width:auto;min-width:100%;font-size:100%;clear:none;float:none;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .infobox-3cols-child{margin:auto}.mw-parser-output .infobox .navbar{font-size:100%}@media screen{html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data:not(.notheme)>div:not(.notheme)[style]{background:#1f1f23!important;color:#f8f9fa}}@media screen and (prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data:not(.notheme)>div:not(.notheme)[style]{background:#1f1f23!important;color:#f8f9fa}}@media(min-width:640px){body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table{display:table!important}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table>caption{display:table-caption!important}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table>tbody{display:table-row-group}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table th,body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table td{padding-left:inherit;padding-right:inherit}}.mw-parser-output .ib-country{border-collapse:collapse;line-height:1.2em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country td,.mw-parser-output .ib-country th{border-top:1px solid #a2a9b1;padding:0.4em 0.6em 0.4em 0.6em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedtoprow .infobox-header,.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedtoprow .infobox-label,.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedtoprow .infobox-data,.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedtoprow .infobox-full-data,.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedtoprow .infobox-below{border-top:1px solid #a2a9b1;padding:0.4em 0.6em 0.2em 0.6em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedrow .infobox-label,.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedrow .infobox-data,.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedrow .infobox-full-data{border:0;padding:0 0.6em 0.2em 0.6em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedbottomrow .infobox-label,.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedbottomrow .infobox-data,.mw-parser-output .ib-country .mergedbottomrow .infobox-full-data{border-top:0;border-bottom:1px solid #a2a9b1;padding:0 0.6em 0.4em 0.6em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country .infobox-header{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .ib-country .infobox-above{font-size:125%;line-height:1.2}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-names{padding-top:0.25em;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-name-style{display:inline}.mw-parser-output .ib-country .infobox-image{padding:0.5em 0}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-anthem{border-top:1px solid #a2a9b1;padding-top:0.5em;margin-top:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-map-caption{position:relative;top:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-largest,.mw-parser-output .ib-country-lang{font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-ethnic,.mw-parser-output .ib-country-religion,.mw-parser-output .ib-country-sovereignty{font-weight:normal;display:inline}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-fake-li{text-indent:-0.9em;margin-left:1.2em;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-fake-li2{text-indent:0.5em;margin-left:1em;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-website{line-height:11pt}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-map-caption3{position:relative;top:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-fn{text-align:left;margin:0 auto}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-fn-alpha{list-style-type:lower-alpha;margin-left:1em}.mw-parser-output .ib-country-fn-num{margin-left:1em}

|

Dvaravati

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6th–11th century | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| .mw-parser-output .locmap .od{position:absolute}.mw-parser-output .locmap .id{position:absolute;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .locmap .l0{font-size:0;position:absolute}.mw-parser-output .locmap .pv{line-height:110%;position:absolute;text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .locmap .pl{line-height:110%;position:absolute;top:-0.75em;text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .locmap .pr{line-height:110%;position:absolute;top:-0.75em;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .locmap .pv>div{display:inline;padding:1px}.mw-parser-output .locmap .pl>div{display:inline;padding:1px;float:right}.mw-parser-output .locmap .pr>div{display:inline;padding:1px;float:left}@media screen{html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .od,html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .od .pv>div,html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .od .pl>div,html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .od .pr>div{background:#fff!important;color:#000!important}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .locmap img{filter:grayscale(0.6)}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data .locmap div{background:transparent!important}}@media screen and (prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .locmap img{filter:grayscale(0.6)}html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .od,html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .od .pv>div,html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .od .pl>div,html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .od .pr>div{background:white!important;color:#000!important}html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data .locmap div{background:transparent!important}}

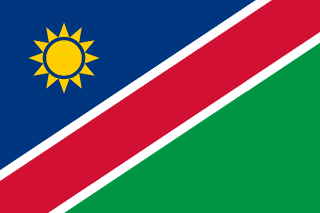

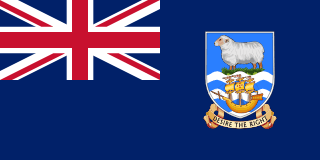

Dvaravati Kingdom/culture and contemporary Asian polities, 800 CE

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| .mw-parser-output .tmulti .multiimageinner{display:flex;flex-direction:column}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{display:flex;flex-direction:row;clear:left;flex-wrap:wrap;width:100%;box-sizing:border-box}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{margin:1px;float:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .theader{clear:both;font-weight:bold;text-align:center;align-self:center;background-color:transparent;width:100%}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbcaption{background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-left{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-right{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .text-align-center{text-align:center}@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti .thumbinner{width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;max-width:none!important;align-items:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow{justify-content:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:100%!important;box-sizing:border-box;text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle .thumbcaption{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .trow>.thumbcaption{text-align:center}}@media screen{html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .tmulti .multiimageinner span:not(.skin-invert-image):not(.skin-invert):not(.bg-transparent) img{background-color:white}}@media screen and (prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .tmulti .multiimageinner span:not(.skin-invert-image):not(.skin-invert):not(.bg-transparent) img{background-color:white}}

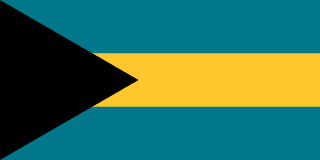

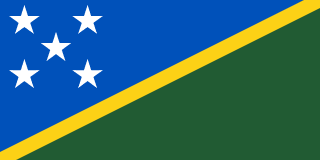

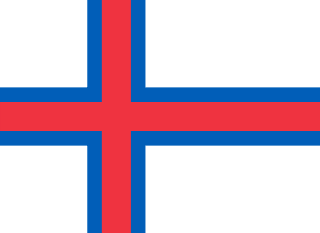

Spread of Dvaravati culture and Mon Dvaravati sites

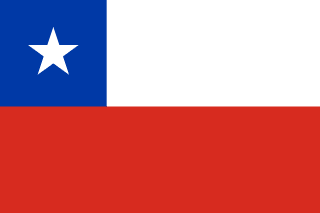

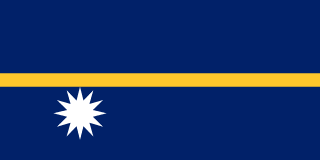

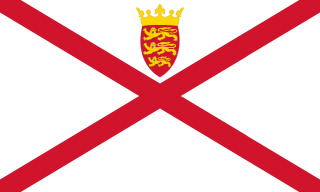

Mon wheel of the law (Dharmacakra), art of Dvaravati period, c. 8th century CE

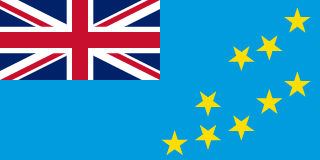

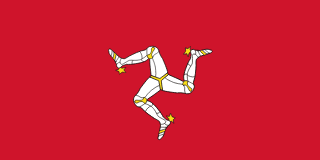

Buddha, art of Dvaravati period, c. 8th-9th century CE

Bronze double denarius of the Gallic Roman emperor Victorinus (269-271 AD) found at U Thong, Thailand

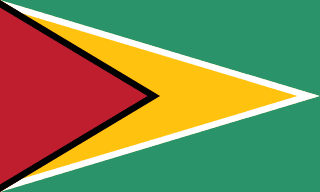

Khao Khlang Nai was a Buddhist sanctuary. The central stupa, rectangular in shape and oriented toward the east, is characteristic of dvaravati architectural style, dated back around 6th-7th century CE.

Khao Khlang Nok, was an ancient Dvaravati-style stupa in Si Thep, dated back around 8th-9th century CE, at present, it is large laterite base.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | .mw-parser-output .plainlist ol,.mw-parser-output .plainlist ul{line-height:inherit;list-style:none;margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .plainlist ol li,.mw-parser-output .plainlist ul li{margin-bottom:0} | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Mon | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Post-classical era | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

6th century | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

11th century | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dvaravati also refers to a culture, an art style, and a disparate conglomeration of principalities of Mon people.[3] The Mon migrants as maritime traders might have brought the Dvaravati Civilization to the Menam Valley around 500 BCE,[12]: 32 which continued to the presence of a “Proto-Dvaravati” period that spans the 4th to 5th centuries, with the existence of the principalities of Chin Lin to the western plain and Tou Yuan to the east, and perhaps earlier.[3]

The center of the early Davaravati was speculated to be Ayojjhapura (present-day Si Thep)[2] or Nakhon Pathom[13]: 10–1 or Avadhyapura (Si Mahosot).[14] Still, the power was shifted to Lavo‘s Lavapura after the annexation of Tou Yuan in 647; some scholars say this transition happened around the 10th and 11th centuries following the fall of Si Thep.[2] However, some argue that Lavapura was potentially a separate kingdom known as the Lavo Kingdom, as mentioned in several historical records, but came under the sphere of Dvaravati influence.[13]: 10–1, 43

The rise of the Angkor in the lower Mekong basin around the 11th–13th centuries,[15] the conquest of Menam Valley and the upper Malay peninsula by Tambralinga‘s king Sujita who also seized Lavo in the mid-10th century,[7]: 283 [16]: 16 the 9-year civil wars in the Angkor in the early 11th century, which led to the devastation of Lavo,[17] as well as the Pagan invasion of Menam Valley around the mid-10th century.[16]: 41 [18]: 4 All of these potentially are the causes of the fall of the Dvaravati civilization.[7]: 283 [16]: 41 Jean Boisselier suggests that after losing influence over the eastern valleys at Lavo to the Angkor in the 10th–11th centuries, Dvaravati kingdoms in the western plain continued until the early 12th century and then probably fell under or influenced[a] by Angkor for a short period during the reign of Jayavarman VII (r.1181–1218).[13]: 262–3 After that, the region entered the Xiān era with the emergence of Suphannabhum, Phrip Phri, and Ayodhya, who later regained influence over Lavo in the 14th century.

The culture of Dvaravati was based around moated cities, the earliest of which appears to be U Thong in what is now Suphan Buri Province. Other key sites include Nakhon Pathom, Phong Tuk, Si Thep, Khu Bua and Si Mahosot, amongst others.[3] The term Dvaravati derives from coins which were inscribed in Sanskrit śrī dvāravatī. The Sanskrit word dvāravatī literally means “that which has gates”.[19]: 301 According to the inscription N.Th. 21 found in 2019 in Wat Phra Ngam in Nakhon Pathom, dated the 6th century, three regional cities were mentioned, including Śrīyānaṁdimiriṅga or Śrīyānaṁdimiriṅgapratipura, then Hastināpurī and Dvāravatī, which made Nakhon Pathom where the fractions was discovered probably the center of Dvāravatī.[20]: 281

The traditional chronology of Dvaravati is mainly based on the Chinese textual account and stylistic comparison by art historians. However, the results from excavations in Chan Sen and Tha Muang mound at U-Thong raise questions about the traditional dating. Newly dated typical Dvaravati cultural items from the site of U-Thong indicate that the starting point of the tradition of Dvaravati culture possibly dates as far back as 200 CE.[21][3] Archaeological, art historical, and epigraphic (inscriptions) evidence all indicate, however, that the main period of Dvaravati spanned the seventh to ninth centuries.[3] Dvaravati culture and influence also spread into Isan and parts of lowland Laos from the sixth century onward. Key sites include Mueang Fa Daet in Kalasin Province, Sema in Nakhon Ratchasima Province, and many others.[22][23]

In the book of I Ching or Yijing, dating to the late 7th century, and the 629–645 journey of a Chinese monk, Xuanzang, placed Dvaravati to the east of Kamalanka or Lang-ya-hsiu and west of Isanapura, if Kamalanka was centered at the ancient Nakhon Pathom as several scholars cited, thus, Dvaravati must be moved to the eastern side of the central plain.[24]: 181–3 This conforms with the location provided in the largest Chinese leishu, Cefu Yuangui, compiled in 1005, says that Dvaravati was to the west of Chenla and the east of the Ge Luo She Fen Kingdom (哥罗舍分国), which was proposed to be centered at the ancient Nakhon Pathom, same as Kamalanka, by Thai historian Piriya Krairiksh, who also identified this kingdom as the Gē Luó Kingdom (哥罗国) in the New Book of Tang,[25]: 59 that also says Dvaravati met the sea (Bay of Bangkok) to the west, adjoin Chenla to the east, and encounter Canasapura to the north.[26] However, according to archaeological evidence found in the western Menam Valley, several scholars suggest Nakhon Pathom was potentially the center of the Dvaravati Kingdoms.[13]: 43

Chinese historian, Chen Jiarong (陳佳榮), claims that the Zhū Jiāng Kingdom in the Cefu Yuangui and Book of Sui was Dvaravati principality,[27] but some scholar placed Zhū Jiāng in the Mun Basin in the Phayakkhaphum Phisai–Nadun–Kaset Wisai cluster to the north of Chenla with the supra-regional center at Champasri.[28]: 45 Zhū Jiāng and Cān Bàn Kingdom established relations with Zhenla via royal intermarriage after the annexation of Funan in 627.[29] Subsequently, they wage wars against Tou Yuan to the northwest. Tou Yuan was the Lavo‘s predecessor that became Dvaravati vassal in 647.[30]: 15–16 [31] Several kingdoms were involved in the conflicts between Dvaravati and Chenla, including the three brother states of Qiān Zhī Fú, Xiū Luó Fēn, and Gān Bì, who collectively fielded over 50,000 elite soldiers, by aligning with the faction that offered the greatest advantage.[14]: 54–5 Certain battles may have been associated with the wars between Lavo and its northern sister Monic kingdom, Haripuñjaya, occurring in the early 10th century,[14]: 36–7 which also weakened Dvaravati Kamalanka.[16]: 105

A mixed Sanskrit–Khmer inscription dated 937 documents a line of princes of Canasapura, one of the Dvaravati polities, started by a Bhagadatta and ended by a Sundaravarman and his sons Narapatisimhavarman and Mangalavarman.[8]: 122 Further east, the Chinese Tang Huiyao mentions the kingdom of Keoi Lau Mì of the Kuy people[32] was also influenced by Dvaravati.[33] In the early 10th century, several Dvaravati polities in the Menam Valley, which were weakened by decade-long wars between two Mon kingdoms, Hariphunchai and Lavo, fell to the invasion by Tambralinga, then by the Chola and Pagan in the late 10th century. Later, Dvaravati polities began to come under constant attacks and aggression of the Khmer Empire, and central Southeast Asia was ultimately invaded by King Suryavarman II in the first half of the 12th century.[34] Hariphunchai survived its southern progenitors until the late 13th century, when it was incorporated into Lan Na.[35]

During the decline period of Dvaravati, its succeeded polity,[36] mentioned as Xiān (暹) by several Chinese and Đại Việt sources, was formed in the lower Menam Basin around the 11th century.[37]: 46 This new polity evolved into the Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1351.[1] Its capital’s full name also referred to Dvaravati as the former capital; Krung Thep Dvaravati Si Ayutthaya (กรุงเทพทวารวดีศรีอยุธยา).[38][39][40][41] All former Dvaravati principalities, including Lavo, Suphannabhum, and the northern cities of the Sukhothai Kingdom, were later incorporated into the Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1388, 1424, and 1438, respectively.[42]: 274

According to the Burmese Inscription of Hsinbyushin of Ava A.D. 1768 (Serial No. 1128),[43] which was found on a bronze gun at Shwezigon Pagoda, and acquired by the Burmese in 1767, the Burmese continued to refer to Ayutthaya as Dvaravati[44] by describing the “conquest of Dvāravati (Siam)“[43] even after its fall to a Burmese invasion during the Pagan Kingdom. Several genetic studies published in the 2020s also founded the relations between the Mon people and Siamese people (Central Thai people) who were the descendants of the Ayutthaya.[45][46] The Laotian Phra That Phanom Chronicle also refers to Ayodhya before the traditional formation of the Ayutthaya Kingdom as Dvaravati and Sri Ayodhiya Dvaravati Nakhon (ศรีอโยธิยาทวารวดีนคร).[47]

Little is known about the administration of Dvaravati. It might simply have been a loose gathering of chiefdoms rather than a centralised state, expanding from the coastal area of the upper peninsula to the riverine region of Chao Phraya River. Hinduism and Buddhism were significant. There are 107 Dvaravati cities in Thailand, most of which are in the central plain.[48]: 66 The three largest settlements appear to have been at Nakhon Pathom, Suphanburi, and Phraek Si Racha, with additional centers at U Thong, Chansen, Khu Bua, Pong Tuk, Mueang Phra Rot, Lopburi, Si Mahosot, Kamphaeng Saen, Dong Lakhon, U-Taphao, Ban Khu Mueang, and Si Thep.[19]: 303–312

According to the Chinese records during the Tang dynasty, Dvaravati is divided into three regions; possibly Kamalanka at Nakhon Pathom which has been identified as the center of Dvaravati culture, former Chin Lin at Mueang Uthong, and the last one at Si Mahosot of Avadhyapura. Many government officials, such as military generals and civil servants, administer the national affairs.[49]: 55 Dvaravati has two vassal kingdoms, including Tou Yuan (陀垣) the Lavo predecessor, and an island kingdom Tanling (曇陵),[30]: 15–16 [31]: 27 whose exact location remains unknown; it was potentially located on some island or small peninsula in the swamp area of the early historic Bay of Bangkok.[30]: 15–16

A study on Dvaravati settlement patterns before the 14th century in the upper Chi–Mun basins suggests that Dvaravati might have been made up of several kingdoms linked by trade networks and centered at supra-regional level settlements, such as Dong Mueang Aem, Phimai, Mueang Fa Daet Song Yang, Mueang Sema, Non Mueang, and Si Thep;[50]: 151–152 similar to in the Menam Valley.[51] A 2015 study of the pre-600 CE circular moated settlements in the Mun Valleys found that the sites were concentrated into five groups; the westernmost and smallest group with a total of 4 settlemets is the Mueang Sema circle. To the east is the Phimai cluster which has a larger number of settlements than the other groups. Next is the group of Phayakkhaphum Phisai–Nadun–Kaset Wisai on the northern Mun watershed with the well known site at Champasri, which has been identified as the Zhū Jiāng Kingdom or later Zhān Bó. To the south is the Buriram–Surin group, which has almost the same size in terms of number of settlements and predicted mean size as the third group. The last cluster is the easternmost on the adjoined watershed of the Mun–Chi Rivers, with the most concentrated area in Suwannaphum, Phon Sai, and Nong Hi of Roi Et province.[52]: 8–9

The following shows the polities under Dvaravati culture in the Menam and the Chi–Mun Valleys during the first millennium.

|

|

Seat/Cluster | Level | Settlements | Identified as | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menam Basin | |||||||||||

| Nakhon Pathom | Supra-regional center | 8 | Kamalanka (Sambuka; 6th-c. Dvaravati) | ||||||||

| Si Thep | Supra-regional center | Qiān Zhī Fú[14] | |||||||||

| Uthong/Suphanburi | Regional center | 9 | Chin Lin (Proto-Dvaravati)/She Ba Ruo | ||||||||

| Phraek Si Racha | Regional center | 12[b]/30[c] | Duō Miè?[d] | ||||||||

| Lopburi | District center | 14 | Tou Yuan (Proto-Dvaravati)[14]: 54 /Lavo | ||||||||

| Si Mahosot | District center | 7 | Avadhyapura (6th-c. Dvaravati[14]) | ||||||||

| Khao Laem, Uthai Thani | Sub-district center | 6 | Bō Cì? (波刺) | ||||||||

| Tha Tako, Nakhon Sawan | Sub-district center | 8 | Part of Qiān Zhī Fú?[14]: 34 /Xiū Luó Fēn? | ||||||||

| Utapao, Saraburi | Sub-district center | 4 | Part of Lavo | ||||||||

| Chaliang | Sub-district center | 4 | Mueang Chaliang | ||||||||

| Yommarad | Sub-district center | 3 | Part of Qiān Zhī Fú?[14]: 34 /Xiū Luó Fēn? | ||||||||

| Tri Trueng | Sub-district center | 3 | |||||||||

| Mun–Chi Basins | |||||||||||

| Dong Mueang Aem | Supra-regional center | Unknown | |||||||||

| Phimai | Supra-regional center | 103 | Mahidharapura (Vimayapura) | ||||||||

| Mueang Sema | Regional center | 4 | Canasapura (8th-c. Dvaravati) | ||||||||

| Dvaravati kingdoms in the Menam Valley. | Champasri | Regional center | 69 | Zhū Jiāng?,[28]: 45 or Zhān Bó/[14]: 45 Yamanadvipa, Vassal of Wen Dan[53] or Bhavapura[28]: 56 |

|||||||

|

|

Phayakkhaphum Phisai– Nadun–Kaset Wisai |

||||||||||

| Fa Daet Song Yang | District center | Wen Dan[53] or Bhavapura[28]: 59 |

|||||||||

| Kantharawichai | District center | ||||||||||

| Non Mueang | Sub-district center | 10 | Part of Bhavapura?[28]: 123 or Wen Dan? | ||||||||

| Buriram–Surin | 57 | Part of Vimayapura?/Mahidharapura? | |||||||||

| Suwannaphum–Nong Hi | 39 | Part of Bhavapura?[28]: 56 | |||||||||

| Phon | Pó Àn (婆岸)[14]: 30 | ||||||||||

| Dvaravati polities in the upper Chi River Basin | Songkhram–Mekhong Basins | ||||||||||

|

|

Nakhon Phanom/Thakhek | Changzhou of the Tang,[14]: 45 Na Lao[14]: 45 /Later Gotapura |

|||||||||

| Sakhon Nakhon | Changzhou of the Tang,[14]: 45 Later Mahidharapura? |

||||||||||

| Phu Phrabat/Vientiane | Dōu Hē Lú (都訶盧)?[14]: 45 | ||||||||||

| Savannakhet–Mukdahan | Gān Bì (甘毕)[14]: 46 | ||||||||||

| Dvaravati-influenced kingdoms with uncertain identification | |||||||||||

| .mw-parser-output .hlist dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul{margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt,.mw-parser-output .hlist li{margin:0;display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ul{display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist .mw-empty-li{display:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dt::after{content:”: “}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li::after{content:” · “;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li:last-child::after{content:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:first-child::before{content:” (“;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:last-child::after{content:”)”;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol{counter-reset:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li{counter-increment:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li::before{content:” “counter(listitem)”a0 “}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li ol>li:first-child::before{content:” (“counter(listitem)”a0 “} | |||||||||||

| Clusters of 7th-c. moated sites in Mun Valley |

|

||||||||||

The excavation in several sites found silver coins dated the 7th century that mentioned the king and queen of the kingdom written in Sanskrit with Pallava script: śrīdvaravatīsvarapunya (King Sridvaravati, who has great merit) and śrīdvaravatīsvaradevīpuṇya (the goddess of the meritorious King Dvaravati).[54] In addition, the copper plate dating from the 6th–mid 7th centuries found at U Thong also mentions King Harshavarman (หรรษวรมัน), who was assumed by Jean Boisselier to be one of the kings of Dvaravati, while George Cœdès considered the plate was brought from the Khmer Empire, and the name mentioned might be the Khmer king as well.[55] However, the periods seem unrelated since King Harshavarman I of Khmer reigned from 910–923, 200 years later than the age of the inscription,[56][57] and Harshavarman I’s grandfather was Indravarman I,[58][59][60] not Isanavarman as the inscription mentioned.[55]

Moreover, the inscription found in Ban Wang Pai, Phetchabun province (K. 978), dated 550 CE, also mentions the enthronement of the Dvaravati ruler, who was also a son of Prathivindravarman, father of Bhavavarman I of Chenla, which shows the royal lineage relation between Dvaravati and Chenla. However, the name of such a king was missing.[61] The other king was mentioned in the Nern Phra Ngam inscription, found in Nakhon Pathom province, dated mid 5th – mid 6th centuries CE but the name was missing as well.[62]

However, some research suggests Bhavavarman mentioned in the Ban Wang Pai inscription of Si Thep may not be Bhavavarman I of Chenla due to different inscription styles.[63]: 17–19

The following chart shows the dynastic relation between Dvaravati polities and other kingdoms in the Chao Phraya–Mekong Valleys

| Royal relation between Dvaravati polities and other kingdoms in the Chao Phraya–Mekong Valleys | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chin Lin

| Ruler | Reign | Note | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rulers before Isanavarman remain unknown. | ||||

| Isanavarman[55] | 5th–6th c. | |||

| Unknown[55] | 5th–6th c. | Son of the previous | ||

| Harshavarman[55] | mid-6th c. | Son of the previous. | ||

| Maratha?[67]: 12 [68]: 97 | late 9th c. | |||

Kamalanka

| Name | Reign | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Thai | ||

| Kakabatr/Sakata/Sakkorndam/Siddhijaya Brahmadeva[25]: 12 | กากะพัตร/สกตา/สักกรดำ/สิทธิไชยพรหมเทพ | 566–638 | Founder.[25]: 11 As king of Takkasila (Nakhon Pathom) |

| Pu xie qi yao[13]: 130 (Siddhijaya?) | As king of Tuo-he-luo (Dvaravati) | ||

| Kalavarnadishraj | กาฬวรรณดิศ/ กาวัณดิศราช | 638–648 | Later King of Lavo (r. 648–700) |

| Si Sap[69] | ศรีทรัพย์ | 648?–? | ฺSon of Kakabatr. Based on a local fable. |

| Pú-jiā-yuè-mó | late 7th cent.? | As king of Gē Luó Shě Fēn | |

| Mǐ-shī-bō-luó Shǐ-lì-pó-luó | early 8 cent.? | As king of Gē Luó Fù Shā Luó | |

| Sikaraj[25]: 15 | สิการาช | late 8th cent.–807 | Based on legends. |

| Phraya Kong[25]: 15 | พระยากง | 807–867 | Son of the previous. Based on legends. |

| Phraya Pan[25]: 15 | พระยาพาน | 867–913[70]: 67 | Later King of Haripuñjaya (r. 899, 913–916) |

| King of Phetchaburi (Later Kingdom of Phrip Phri) (unknown regnal title)[64]: 60–1 | 913–927? | Usurper. Adoptive father of the previous. | |

Qiān Zhī Fú

.mw-parser-output .defaultleft{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .defaultcenter{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .defaultright{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .col1left td:nth-child(1),.mw-parser-output .col2left td:nth-child(2),.mw-parser-output .col3left td:nth-child(3),.mw-parser-output .col4left td:nth-child(4),.mw-parser-output .col5left td:nth-child(5),.mw-parser-output .col6left td:nth-child(6),.mw-parser-output .col7left td:nth-child(7),.mw-parser-output .col8left td:nth-child(8),.mw-parser-output .col9left td:nth-child(9),.mw-parser-output .col10left td:nth-child(10),.mw-parser-output .col11left td:nth-child(11),.mw-parser-output .col12left td:nth-child(12),.mw-parser-output .col13left td:nth-child(13),.mw-parser-output .col14left td:nth-child(14),.mw-parser-output .col15left td:nth-child(15),.mw-parser-output .col16left td:nth-child(16),.mw-parser-output .col17left td:nth-child(17),.mw-parser-output .col18left td:nth-child(18),.mw-parser-output .col19left td:nth-child(19),.mw-parser-output .col20left td:nth-child(20),.mw-parser-output .col21left td:nth-child(21),.mw-parser-output .col22left td:nth-child(22),.mw-parser-output .col23left td:nth-child(23),.mw-parser-output .col24left td:nth-child(24),.mw-parser-output .col25left td:nth-child(25),.mw-parser-output .col26left td:nth-child(26),.mw-parser-output .col27left td:nth-child(27),.mw-parser-output .col28left td:nth-child(28),.mw-parser-output .col29left td:nth-child(29),.mw-parser-output .col-1left td:nth-last-child(1),.mw-parser-output .col-2left td:nth-last-child(2),.mw-parser-output .col-3left td:nth-last-child(3),.mw-parser-output .col-4left td:nth-last-child(4),.mw-parser-output .col-5left td:nth-last-child(5),.mw-parser-output .col-6left td:nth-last-child(6),.mw-parser-output .col-7left td:nth-last-child(7),.mw-parser-output .col-8left td:nth-last-child(8),.mw-parser-output .col-9left td:nth-last-child(9){text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .col1center td:nth-child(1),.mw-parser-output .col2center td:nth-child(2),.mw-parser-output .col3center td:nth-child(3),.mw-parser-output .col4center td:nth-child(4),.mw-parser-output .col5center td:nth-child(5),.mw-parser-output .col6center td:nth-child(6),.mw-parser-output .col7center td:nth-child(7),.mw-parser-output .col8center td:nth-child(8),.mw-parser-output .col9center td:nth-child(9),.mw-parser-output .col10center td:nth-child(10),.mw-parser-output .col11center td:nth-child(11),.mw-parser-output .col12center td:nth-child(12),.mw-parser-output .col13center td:nth-child(13),.mw-parser-output .col14center td:nth-child(14),.mw-parser-output .col15center td:nth-child(15),.mw-parser-output .col16center td:nth-child(16),.mw-parser-output .col17center td:nth-child(17),.mw-parser-output .col18center td:nth-child(18),.mw-parser-output .col19center td:nth-child(19),.mw-parser-output .col20center td:nth-child(20),.mw-parser-output .col21center td:nth-child(21),.mw-parser-output .col22center td:nth-child(22),.mw-parser-output .col23center td:nth-child(23),.mw-parser-output .col24center td:nth-child(24),.mw-parser-output .col25center td:nth-child(25),.mw-parser-output .col26center td:nth-child(26),.mw-parser-output .col27center td:nth-child(27),.mw-parser-output .col28center td:nth-child(28),.mw-parser-output .col29center td:nth-child(29),.mw-parser-output .col-1center td:nth-last-child(1),.mw-parser-output .col-2center td:nth-last-child(2),.mw-parser-output .col-3center td:nth-last-child(3),.mw-parser-output .col-4center td:nth-last-child(4),.mw-parser-output .col-5center td:nth-last-child(5),.mw-parser-output .col-6center td:nth-last-child(6),.mw-parser-output .col-7center td:nth-last-child(7),.mw-parser-output .col-8center td:nth-last-child(8),.mw-parser-output .col-9center td:nth-last-child(9){text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .col1right td:nth-child(1),.mw-parser-output .col2right td:nth-child(2),.mw-parser-output .col3right td:nth-child(3),.mw-parser-output .col4right td:nth-child(4),.mw-parser-output .col5right td:nth-child(5),.mw-parser-output .col6right td:nth-child(6),.mw-parser-output .col7right td:nth-child(7),.mw-parser-output .col8right td:nth-child(8),.mw-parser-output .col9right td:nth-child(9),.mw-parser-output .col10right td:nth-child(10),.mw-parser-output .col11right td:nth-child(11),.mw-parser-output .col12right td:nth-child(12),.mw-parser-output .col13right td:nth-child(13),.mw-parser-output .col14right td:nth-child(14),.mw-parser-output .col15right td:nth-child(15),.mw-parser-output .col16right td:nth-child(16),.mw-parser-output .col17right td:nth-child(17),.mw-parser-output .col18right td:nth-child(18),.mw-parser-output .col19right td:nth-child(19),.mw-parser-output .col20right td:nth-child(20),.mw-parser-output .col21right td:nth-child(21),.mw-parser-output .col22right td:nth-child(22),.mw-parser-output .col23right td:nth-child(23),.mw-parser-output .col24right td:nth-child(24),.mw-parser-output .col25right td:nth-child(25),.mw-parser-output .col26right td:nth-child(26),.mw-parser-output .col27right td:nth-child(27),.mw-parser-output .col28right td:nth-child(28),.mw-parser-output .col29right td:nth-child(29),.mw-parser-output .col-1right td:nth-last-child(1),.mw-parser-output .col-2right td:nth-last-child(2),.mw-parser-output .col-3right td:nth-last-child(3),.mw-parser-output .col-4right td:nth-last-child(4),.mw-parser-output .col-5right td:nth-last-child(5),.mw-parser-output .col-6right td:nth-last-child(6),.mw-parser-output .col-7right td:nth-last-child(7),.mw-parser-output .col-8right td:nth-last-child(8),.mw-parser-output .col-9right td:nth-last-child(9){text-align:right}

| Name | Reign | Title | Note | Source(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romanized | Thai | |||||

| Chakravantin | จักรวรรติน | Unknown | King of Si Thep (Ayodhyapura?) | Father of Prathivindravarman | Wang Pai Inscription (K.978)[61] | |

| Prathivindravarman | ปฤถิวีนทรวรมัน | ?–550 | Father of Bhavavarman I of Chenla? | |||

| Unknown or Bhavavarman[e] | 550–? | Son of Prathivindravarman | ||||

| Ramaraj | รามราช | c. 662 | King of Ramburi (Ayodhyapura?/Mawlamyine?) | Spouse of Haripuñjaya‘s queen Camadevi | Jinakalamali[65] | |

| Rulers after the reign of Ramaraj are still unknown. | ||||||

| The influence of Chenla probably ended when Chenla faced the power struggle which led to kingdom division in the late 7th century during the reign of Jayadevi. | ||||||

| Adītaraj | อาทิตยราช | late 800s | King of Ayojjhapura | Adversary of Yasodharapura | Ratanabimbavamsa[71]: 51 | |

| Rajathirat | ราชาธิราช | before 946 | Jinakalamali[2] | |||

| Rulers before the reign of Vap Upendra are still unknown. | ||||||

| Vap Upendra | วาป อุเปนทร | 949-? | Governor of Rāmaññadesa | Relative of Rajendravarman II of Ankor | Rajendravarman II Inscription[62]: 3546 | |

Lavo

| Name | Reign | Notes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Thai | ||||

| Kalawandith | กาฬวรรดิษฐ์ | 648–700 | Founder. Son of Takkasila‘s king, Kakapat. | ||

| Unknown | 8th–9th century | ||||

| Uchitthaka Chakkawat | อุฉิฎฐกะจักรวรรดิ | ?–927 | Later became King of Haripuñjaya | ||

| Sujita[72] | สุชิตราช | 927–930 | Also King of Tambralinga. As a tributary state of Tambralinga. | ||

| Kampoch[72] | กัมโพช | 930–946? | Son of the previous. As a tributary state of Tambralinga.[73][74] | ||

| Vacant? | 946–948 | ||||

| Vap Upendra? | วาป อุเปนทร | 949–960s? | As the governor of Rāmaññadesa, appointed by Rajendravarman II.[62]: 3546 | ||

| Narapativiravarman? | 960s?–1001? | As the governor. | |||

| Lakshmipativarman[75] | ศรีลักษมีปติวรมัน | 1006–? | As the governor, appointed by Suryavarman I[75] | ||

| Laparaja[76]: 208–10 | ลพราช | Period of constant wars against Haripuñjaya. | |||

| Unknown[76]: 211 | ?–1052? | Son of the previous. | |||

| Chandachota | จันทรโชติ | 1052–1069 | Prince of Suphannabhum who fled to Haripuñjaya after Suphannabhum was seized by Tambralinga in the 920s. | ||

Dvaravati itself was heavily influenced by Indian culture, and played an important role in introducing Buddhism and particularly Buddhist art to the region. Stucco motifs on the religious monuments include garudas, makaras, and Nāgas. Additionally, groups of musicians have been portrayed with their instruments, prisoners, females with their attendants, soldiers indicative of social life. Votive tablets have also been found, also moulds for tin amulets, pottery, terracotta trays, and a bronze chandelier, earrings, bells and cymbals.[19]: 306–308

.mw-parser-output .reflist{margin-bottom:0.5em;list-style-type:decimal}@media screen{.mw-parser-output .reflist{font-size:90%}}.mw-parser-output .reflist .references{font-size:100%;margin-bottom:0;list-style-type:inherit}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns-2{column-width:30em}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns-3{column-width:25em}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns{margin-top:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns ol{margin-top:0}.mw-parser-output .reflist-columns li{page-break-inside:avoid;break-inside:avoid-column}.mw-parser-output .reflist-upper-alpha{list-style-type:upper-alpha}.mw-parser-output .reflist-upper-roman{list-style-type:upper-roman}.mw-parser-output .reflist-lower-alpha{list-style-type:lower-alpha}.mw-parser-output .reflist-lower-greek{list-style-type:lower-greek}.mw-parser-output .reflist-lower-roman{list-style-type:lower-roman}

-

Several cities in the western valleys are listed in the religious-related Preah Khan Inscription but no political or military action made by the Angkorian kings was mentioned. In contrast, several Siamese chronicles mention numbers of dynastic movements in the region during this period, such as refounding Phrip Phri by Pprappanom Tteleiseri from Soucouttae/Locontàï in 1188, claiming Suphannabhum by U Thong I in 1163, annexation of Chen Li Fu and Phraek Si Racha by Phrip Phri in 1204, and the enthronement as Ayodhya king of U Thong II, prince of Phrip Phri, in 1205.

-

According to Cefu Yuangui

-

If Tou Yuan was the predecessor of the Lavo Kingdom, as proposed by Tatsuo Hoshino,[14]: 54 Duō Miè — which was to the west of Tou Yuan — should be in the area of Phraek Si Racha.

-

If Bhavavarman mentioned in the inscription is not Bhavavarman I and Bhavavarman II of Chenla.[63]: 17–19

-

Calculated from the text given in the chronicle: “สิ้น 97 ปีสวรรคต ศักราชได้ 336 ปี พระยาโคดมได้ครองราชสมบัติอยู่ ณ วัดเดิม 30 ปี”[64]: 30 which is transcribed as “…at the age of 97, he passed away in the year 336 of the Chula Sakarat. Phraya Kodom reigned in the Mueang Wat Derm for 30 years…”.

-

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit;word-wrap:break-word}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:”””””””‘””‘”}.mw-parser-output .citation:target{background-color:rgba(0,127,255,0.133)}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-free.id-lock-free a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/65/Lock-green.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-limited.id-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .id-lock-registration.id-lock-registration a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-subscription.id-lock-subscription a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg”)right 0.1em center/12px no-repeat}body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-free a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-limited a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-registration a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-subscription a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background-size:contain;padding:0 1em 0 0}.mw-parser-output .cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:none;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;color:var(–color-error,#d33)}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{color:var(–color-error,#d33)}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#085;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right{padding-right:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .citation .mw-selflink{font-weight:inherit}@media screen{.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{color:#18911f}}@media screen and (prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{color:#18911f}}“หลักฐานฟ้อง! ทำไมจึงเชื่อได้ว่า “ศรีเทพ” คือศูนย์กลางทวารวดี”. www.silpa-mag.com (in Thai). 13 December 2023. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

-

Pensupa Sukkata (16 June 2022). “ฤๅเมืองโบราณศรีเทพ คือ ‘อโยธยา-มหานคร’ ในตำนานพระแก้วมรกต และตำนานพระสิกขีปฏิมาศิลาดำ?” [Is the ancient city of Sri Thep the ‘Ayutthaya-the metropolis’ in the legend of the Emerald Buddha and the legend of the black stone Buddha Sikhi Patima?]. Matichon (in Thai). Archived from the original on 2024-12-18. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

-

Murphy, Stephen A. (October 2016). “The case for proto-Dvāravatī: A review of the art historical and archaeological evidence”. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 47 (3): 366–392. doi:10.1017/s0022463416000242. ISSN 0022-4634. S2CID 163844418.

-

Khemchart Thepchai (2014). โบราณคดีและประวัติศาสตร์เมืองสุพรรณบุรี [Archaeology and history of Suphan Buri] (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Cyber Roxy Agency Group. p. 114. ISBN 978-9744180896. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 15 December 2024.

-

Stanley J. O’Connor (1970). “Dvāravatī: The Earliest Kingdom of Siam (6th to 11th Century A.D.)”. The Journal of Asian Studies. 29 (2). Duke University Press. Archived from the original on 28 April 2024.

-

Grant Evans (2014). “The Ai-Lao and Nan Chao/Tali Kingdom: A Re-orientation” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

-

Lawrence Palmer Briggs (1950). “The Khmer Empire and the Malay Peninsula”. The Far Eastern Quarterly. 9 (3). Duke University Press: 256–305. doi:10.2307/2049556. JSTOR 2049556. Archived from the original on 26 April 2024.

-

Indrawooth, Phasook. Dvaravati: Early Buddhist Kingdom in Central Thailand (PDF).

-

ศิริพจน์ เหล่ามานะเจริญ (4 February 2022). “ทวารวดี ในบันทึกของจีน”. Matichon (in Thai). Archived from the original on 28 April 2024. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

-

“中國哲學書電子化計劃: 《陳書》卷六本紀第六後主” [Chinese Philosophy Text Digitalization Project: Book of Chen, Volume 6 Chronicles of the Sixth Emperor]. ctext.org/zh (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2025-05-19. Retrieved 20 May 2025. Text: 十二月丙辰,頭和國遣使獻方物。司空長沙王叔堅有罪免。戊午夜,天開自西北至東南,其內有青黃色,隆隆若雷聲。

-

Thanutchaporn Ketkong; Supat Chaiwan (2021). “Dvaravati Civilization Footprints, Its Maximus Creeds and Cultures in Siam Suvarnbhumi, Ancient Thailand”. Global Interactive Journal of World Religions and Cultures. 1 (1): 28–41.

-

Saritpong Khunsong (November 2015). ทวารวดี: ประตูสู่การค้าบนเส้นทางสายไหมทางทะเล [Dvaravati: The Gateway to Trade on the Maritime Silk Road] (in Thai). Paper Met Co., Ltd. ISBN 978-974-641-577-4.

-

Hoshino, T (2002). “Wen Dan and its neighbors: the central Mekong Valley in the seventh and eighth centuries.”. In M. Ngaosrivathana; K. Breazeale (eds.). Breaking New Ground in Lao History: Essays on the Seventh to Twentieth Centuries. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. pp. 25–72.

-

Srisakara Vallipotama, “ละโว้ / Lavo” [Thai with English summary], Warasan Muang Boran – วารสารเมืองโบราณ (Muang Boran/Archaeology Journal) vol.1, no.3, April-June 1975, pp.42-65, 116.

-

Fine Arts Department. โบราณวิทยาเรื่องเมืองอู่ทอง [Archaeology of U Thong City] (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok. p. 232. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-11-10.

-

“เมื่อ ลวปุระ-ลพบุรี ถูกพระเจ้าสุริยวรมันที่ 1 ยกทัพบุกทำลายจนมีสภาพเป็นป่า” [When Lopburi was invaded and destroyed by King Suryavarman I until it became a forest.]. www.silpa-mag.com (in Thai). 6 November 2023. Archived from the original on 2023-11-06. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

-

Warunee Osatharom (1997). “วิวัฒนาการเมืองสุพรรณ: การศึกษาการพัฒนาชุมชนเมืองจากพุทธศตวรรษที่ 6 – ต้นพุทธศตวรรษที่ 24” [The evolution of Suphanburi: A study of urban community development from the 6th Buddhist century to the beginning of the 24th Buddhist century] (PDF) (in Thai).

-

Higham, C., 2014, Early Mainland Southeast Asia, Bangkok: River Books Co., Ltd., ISBN 9786167339443

-

Dominic Goodall; Nicolas Revire (2021). “East and West – New Inscriptions from Funan, Zhenlaand Dvāravatī”. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient. 107: 257–321. doi:10.3406/befeo.2021.6376. JSTOR 27164175. Archived from the original on 2023-09-25.

-

Glover, I. (2011). The Dvaravati Gap-Linking Prehistory and History in Early Thailand. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, 30, 79-86.

-

Murphy, Stephen A. (2013). “Buddhism and its Relationship to Dvaravati Period Settlement Patterns and Material Culture in Northeast Thailand and Central Laos c. Sixth–Eleventh Centuries AD: A Historical Ecology Approach to the Landscape of the Khorat Plateau”. Asian Perspectives. 52 (2): 300–326. doi:10.1353/asi.2013.0017. hdl:10125/38732. ISSN 1535-8283. S2CID 53315185.

-

Pichaya Svasti (2013). “Dvaravati art in Isan”. Bangkok post. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

-

Chand Chirayu Rajani. “Background to the Sri Vijaya Story – Part I” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2020.

-

Saritpong Khumsong (2014). โบราณคดีเมืองนครปฐม: การศึกษาอดีตศูนย์กลางแห่งทวารวดี [Nakhon Pathom Archaeology: A Study of the Former Center of Dvaravati] (PDF) (in Thai). Bangkok: Papermet (Thailand). p. 230. ISBN 978-974-641-498-2.

-

Sujit Wongthes (6 February 2022). “ทวารวดีศรีเทพ คำบอกเล่าจาก ‘ฝรั่งคลั่งสยาม’“ [Dvaravati Sri Thep, an account from a ‘Siam-crazed foreigner’]. Matichon (in Thai). Retrieved 11 August 2025.

-

“朱江”. www.world10k.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2025-05-17. Retrieved 17 May 2025.

-

Lawrence Palmer Briggs (1951). “The Ancient Khmer Empire” (PDF). Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 4 (1): 1–295. doi:10.2307/1005620. JSTOR 1005620.

-

“中国哲学书电子化计划”. ctext.org (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2025-05-16. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

-

Geoffrey Goble (2014). “Maritime Southeast Asia: The View from Tang-Song China” (PDF). ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. pp. 1–19. ISSN 2529-7287. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-06-19.

-

Fukami Sumio. “The Trade Sphere and the Tributary Business of Linyi (林邑) in the 7th Century: An Analysis of the Additional Parts of the Huangwang chuan (環王伝) of the Xintangshu (新唐書)” (PDF) (in Japanese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

-

Thongtham Nathchamnong (November 2012). “แคว้นของชาวกวย-กูย?” [Kingdom of the Kouy People?]. Thang E-Shann (in Thai). 67. ISSN 2286-6418. OCLC 914873242. Archived from the original on 2024-10-07.

-

“The Mon-Dvaravati Tradition of Early North-central Southeast asia”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

-

David K. Wyatt and Aroonrut Wichienkeeo. The Chiang Mai Chronicle, p.33

-

Pensupa Sukkata (16 June 2022). “ฤๅเมืองโบราณศรีเทพ คือ ‘อโยธยา-มหานคร’ ในตำนานพระแก้วมรกต และตำนานพระสิกขีปฏิมาศิลาดำ?” [Is the ancient city of Sri Thep the ‘Ayutthaya-the metropolis’ in the legend of the Emerald Buddha and the legend of the black stone Buddha Sikhi Patima?]. Matichon (in Thai). Archived from the original on 2024-12-18. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

-

Chris Baker; Pasuk Phongpaichit (2 September 2021). “Ayutthaya Rising” (PDF). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–8. doi:10.1017/9781108120197. ISBN 9781108120197. Archived from the original on 22 April 2025. Retrieved 22 April 2025.

-

Boeles, J.J. (1964). “The King of Sri Dvaravati and His Regalia” (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 52 (1): 102–103. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

-

Pongsripian, Winai (1983). Traditional Thai historiography and its nineteenth century decline (PDF) (PhD). University of Bristol. p. 21. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

-

Blagden, C.O. (1941). “A XVIIth Century Malay Cannon in London”. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 19 (1): 122–124. JSTOR 41559979. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

TA-HTAUNG TA_YA HNIT-HSE SHIT-KHU DWARAWATI THEIN YA – 1128 year (= 1766 A.D) obtained at the conquest of Dwarawati (= Siam). One may note that in that year the Burmese invaded Siam and captured Ayutthaya, the capital, in 1767.

-

JARUDHIRANART, Jaroonsak (2017). THE INTERPRETATION OF SI SATCHANALAI (Thesis). Silpakorn University. p. 31. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

Ayutthaya, they still named the kingdom after its former kingdom as “Krung Thep Dvaravati Sri Ayutthaya”.

-

ฉันทัส เพียรธรรม (2017). “Synthesis of Suphannabhume historical Knowledge in Suphanburi Province by Participatory Process” (PDF) (in Thai). Nakhon Ratchasima College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

-

Duroiselle, Charles; Archaeological Survey of Burma (1921). A List of Inscriptions found in Burma, Part I: The list of inscription arranged in the order of their dates. Rangoon: Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma. p. 175. OCLC 220276832

-

“Bronze Gun – 12-pounder bronze Siamese – about early 18th century”. Royal Armouries. Archived from the original on 20 February 2024. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

-

Kutanan, Wibhu; Liu, Dang; Kampuansai, Jatupol; Srikummool, Metawee; Srithawong, Suparat; Shoocongdej, Rasmi; Sangkhano, Sukrit; Ruangchai, Sukhum; Pittayaporn, Pittayawat; Arias, Leonardo; Stoneking, Mark (2021). “Reconstructing the Human Genetic History of Mainland Southeast Asia: Insights from Genome-Wide Data from Thailand and Laos”. Mol Biol Evol. 38 (8): 3459–3477. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab124. PMC 8321548. PMID 33905512.

-

Wibhu Kutanan, Jatupol Kampuansai, Andrea Brunelli, Silvia Ghirotto, Pittayawat Pittayaporn, Sukhum Ruangchai, Roland Schröder, Enrico Macholdt, Metawee Srikummool, Daoroong Kangwanpong, Alexander Hübner, Leonardo Arias Alvis, Mark Stoneking (2017). “New insights from Thailand into the maternal genetic history of Mainland Southeast Asia”. European Journal of Human Genetics. 26 (6): 898–911. doi:10.1038/s41431-018-0113-7. hdl:21.11116/0000-0001-7EEF-6. PMC 5974021. PMID 29483671. Archived from the original on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) -

Yutthaphong Matwises (4 August 2024). “บ้านเมืองอีสาน-สองฝั่งโขง ใน “อุรังคธาตุ” ตำนานพระธาตุพนม” [Northeastern towns and cities on both sides of the Mekong River in “Urankathathu”, the legend of Phra That Phanom]. www.silpa-mag.com (in Thai). Archived from the original on 2025-05-27. Retrieved 28 May 2025.

-

Punthanida Wakadoun (29 May 2024). “The Dvaravati Footprints From The Study From Paleography”. Global Interactive Journal of World Religions and Cultures. 4 (1): 63–77. Retrieved 20 July 2025.

-

Nitta Eiji (2017). “Chapter 3: Formation of Cities and the State of Dvaravati” (PDF). pp. 55–75. Retrieved 21 July 2025.

-

Pariwat Chiamchit; Thanik Lertcharnri (12 July 2019). “การตั้งถิ่นฐานสมัยโบราณในพื้นที่ลุ่มแม่น้ำชีตอนบน ก่อนพุทธศตวรรษที่ 19” [Ancient Settlement Pattern in the Upper Chi River Basin Prior to the 14th Century A.D.] (PDF). Silpakorn University (in Thai). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2025. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

-

Karen M. Mudar (1999). “How Many Dvaravati Kingdoms? Locational Analysis of First Millennium A.D. Moated Settlements in Central Thailand” (PDF). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 18 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1006/jaar.1998.0329.

-

Dougald J.W. O’Reilly; Glen Scott (2015). “Moated sites of the Iron Age in the Mun River Valley, Thailand: New discoveries using Google Earth”. Archaeological Research in Asia. 3: 9–18. doi:10.1016/j.ara.2015.06.001.

-

Tatsuo Hoshino (2002). “Wen Dan and its neighbours: the central Mekong Valley in the seventh and eighth centuries”. In Mayoury Ngaosrivathana; Kennon Breazeale (eds.). Breaking new ground in Lao history: essays on the seventh to twentieth centuries. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024.

-

“จารึกเหรียญเงินทวารวดี (เมืองดงคอน 3)”. sac.or.th (in Thai). Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

-

“จารึกแผ่นทองแดง” (PDF). finearts.go.th (in Thai). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

-

“Book Review: Voices from S-21” Archived 2008-10-12 at the Wayback Machine. The American Historical Review (October 2002).

-

SBS French program. Special Broadcasting Service (December 10, 2007).

-

Bhattacharya, Kamaleswar (2009). A Selection of Sanskrit Inscriptions from Cambodia. In collaboration with Karl-Heinz Golzio. Center for Khmer Studies.

-

Some Aspects of Asian History and Culture by Upendra Thakur. Page 37.

-

Saveros, Pou (2002). Nouvelles inscriptions du Cambodge (in French). Vol. Tome II et III. Paris: EFEO. ISBN 2-85539-617-4.

-

“จารึกบ้านวังไผ่”. db.sac.or.th (in Thai). Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

-

Supitchar Jindawattanaphum (2020). “Evidences of Governors and Aristocrats’ Existences in Dvaravati Period” (PDF) (in Thai). Nakhon Pathom Rajabhat University. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

-

Kangwon Katchima (2019). “จารึกพระเจ้ามเหนทรวรมัน” [The inscriptions of king Mahendravarman] (PDF) (in Thai). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2025.

-

“ใคร?เจ้าชายรามราช” [Who? Prince Ramaraj]. Thai Rath (in Thai). 19 September 2010. Archived from the original on 2024-12-19. Retrieved 19 December 2024.

-

Phanomkorn Navasela (1 May 2018). “นครปฐมเมืองท่าแห่งสหพันธรัฐทวารวดี” [Nakhon Pathom, the port city of the Dvaravati Federation]. Lek-Prapri Viriyahphat Foundation (in Thai). Retrieved 15 July 2025.

-

Walailak Songsiri (2025). “ในดินแดนแห่งเจนลีฟู นครรัฐที่ไม่ได้อยู่ในอำนาจทางการเมืองของพระเจ้าชัยวรมันที่ ๗ สู่ปัญหาทางประวัตศาสตร์ที่หาทางออกไม่เจอของสังคมไทย” [In the land of Chen Li Fu, a city-state that was not under the political power of King Jayavarman VII, to the historical problems that cannot be solved for Thai society.]. Lek-Prapai Viriyahpant Foundation (in Thai). Retrieved 14 July 2025.

-

Piyanan Chobsilpakob; Pratchaya Rungsangthong (2024). “จารึกสมัยทวารวดีในดินแดนฝั่งตะวันตกของประเทศไทย” [Dvaravati inscriptions in the western part of Thailand] (PDF). Fine Arts Department of Thailand (in Thai). pp. 95–100. Retrieved 15 July 2025.

-

“ตำนานเมี่ยงคำ” [Fable of Miang Kham]. cmi.nfe.go.th (in Thai). 18 May 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2025.

-

Thepthani, Phra Borihan (1953). Thai National Chronicles: the history of the nation since ancient times (in Thai). S. Thammasamakkhi. Archived from the original on 5 November 2023. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

-

Pae Talalak (1912). “รัตนพิมพวงษ์” [Ratanabimbavamsa] (PDF) (in Thai). Retrieved 19 December 2024.

-

Lem Chuck Moth (30 December 2017). “The Sri Vijaya Connection”. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

-

เพ็ญสุภา สุขคตะ (28 August 2019). “ปริศนาโบราณคดี l ‘สงครามสามนคร’ (1): กษัตริย์หริภุญไชยผู้พลัดถิ่นหนีไปแถบเมืองสรรคบุรี?” (in Thai). Matichon. Archived from the original on 25 December 2023. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

-

เพ็ญสุภา สุขคตะ (12 September 2019). “ปริศนาโบราณคดี : ‘สงครามสามนคร’ (จบ) : การปรากฏนามของพระเจ้ากัมโพชแห่งกรุงละโว้?” (in Thai). Matichon. Archived from the original on 25 December 2023. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

-

“๑ สหัสวรรษ แห่ง “พระนิยม”“. Fine Arts Department (in Thai). Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

-

“Yonok Chronicle” (PDF) (in Thai). 1936. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- Robert L. Brown, The Dvaravati Wheels of the Law and the Indianization of South East Asia. Studies in Asian Art and Archaeology, Vol. 18, Fontein, Jan, ed. Leiden and New York: E. J. Brill, 1996.

- Elizabeth Lyons, “Dvaravati, a Consideration of its Formative Period”, R. B. Smith and W. Watson (eds.), Early South East Asia: Essays in Archaeology, History and Historical Geography, Oxford University Press, New York, 1979, pp. 352–359.

- Dhida Saraya, (Sri) Dvaravati: the Initial Phase of Siam’s History, Bangkok, Muang Boran, 1999, ISBN 974-7381-34-6

- Swearer, Donald K. and Sommai Premchit. The Legend of Queen Cama: Bodhiramsi’s Camadevivamsa, a Translation and Commentary. New York: State University of New York Press, 1998. ISBN 0-7914-3776-0

- สุรพล ดำริห์กุล, ประวัติศาสตร์และศิลปะหริภุญไชย, กรุงเทพฯ: สำนักพิมพ์เมืองโบราณ, 2004, ISBN 974-7383-61-6.

- Pierre Dupont, The Archaeology of the Mons of Dvāravatī, translated from the French with updates and additional appendices, figures and plans by Joyanto K.Sen, Bangkok, White Lotus Press, 2006.

- Jean Boisselier, “Ū-Thòng et son importance pour l’histoire de Thaïlande [et] Nouvelles données sur l’histoire ancienne de Thaïlande”, Bōrānwitthayā rư̄ang MỮang ʻŪ Thō̜ng, Bangkok, Krom Sinlapakon, 2509 [1966], pp. 161–176.

- Peter Skilling, “Dvaravati: Recent Revelations and Research”, Dedications to Her Royal Highness Princess Galyani Vadhana Krom Luang Naradhiwas Rajanagarindra on her 80th birthday, Bangkok, The Siam Society, 2003, pp. 87–112.

- Natasha Eilenberg, M.C. Subhadradis Diskul, Robert L. Brown (editors), Living a Life in Accord with Dhamma: Papers in Honor of Professor Jean Boisselier on his Eightieth Birthday, Bangkok, Silpakorn University, 1997.

- C. Landes, “Pièce de l’époque romaine trouvé à U-Thong, Thaïlande”, The Silpakorn Journal, vol.26, no.1, 1982, pp. 113–115.

- John Guy, Lost Kingdoms: Hindu Buddhist Sculpture of Early Southeast, New York and Bangkok, Metropolitan Museum of Art and River Books, 2014, p. 32.

- Wārunī ʻŌsathārom. Mư̄ang Suphan bon sēnthāng kan̄plīanplǣng thāng prawattisāt Phutthasattawat thī 8 – ton Phutthasattawat thī 25 (History, development, and geography of the ancient city of Suphan Buri Province, Central Thailand, 8th–25th B.E.), Samnakphim Mahāwitthayālai Thammasāt, Krung Thēp, 2547.

- Supitchar Jindawattanaphum (2020). “หลักฐานการมีอยู่ของผู้ปกครอง และชนชั้นสูงสัมยทวารวดี” [Evidences of Governors and Aristocrats’ Existences in Dvaravati Period] (PDF) (in Thai). Nakhon Pathom Rajabhat University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2024.

pcs.c1.Page.onBodyEnd();

Source: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA 4.0. Changes may have been made. See authors on source page history.

Eksplorasi konten lain dari Tinta Emas

Berlangganan untuk dapatkan pos terbaru lewat email.