B-10 recoilless rifle

Soviet recoilless gun

The B-10 recoilless rifle (Bezotkatnojie orudie-10, known as the RG82 in East Germany)[7] is a Soviet 82 mm smoothbore recoilless gun.[8] It could be carried on the rear of a BTR-50 armoured personnel carrier. It was a development of the earlier SPG-82, and entered Soviet service during 1954. It was phased out of service in the Soviet Army in the 1960s and replaced by the SPG-9, remaining in service with parachute units at least until the 1980s. Although now obsolete it was used by many countries during the Cold War.[9][10]

.mw-parser-output .infobox-subbox{padding:0;border:none;margin:-3px;width:auto;min-width:100%;font-size:100%;clear:none;float:none;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .infobox-3cols-child{margin:auto}.mw-parser-output .infobox .navbar{font-size:100%}@media screen{html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data:not(.notheme)>div:not(.notheme)[style]{background:#1f1f23!important;color:#f8f9fa}}@media screen and (prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data:not(.notheme)>div:not(.notheme)[style]{background:#1f1f23!important;color:#f8f9fa}}@media(min-width:640px){body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table{display:table!important}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table>caption{display:table-caption!important}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table>tbody{display:table-row-group}body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table th,body.skin–responsive .mw-parser-output .infobox-table td{padding-left:inherit;padding-right:inherit}}

| B-10 recoilless rifle | |

|---|---|

|

B-10 recoilless rifle in Batey ha-Osef Museum, Israel.

|

|

| Type | Recoilless rifle |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1954–1980s (USSR) |

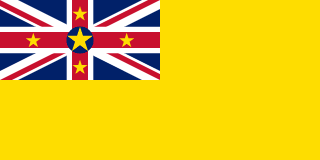

| Used by | Soviet Union other users |

| Wars | Vietnam War[1] Cambodian Civil War Laotian Civil War Yom Kippur War[2] Portuguese Colonial War Lebanese Civil War[3] Western Sahara War Angolan Civil War[4] Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency Iran–Iraq War Somali Civil War[5] Gulf War Third Sudanese Civil War Libyan Civil War[6] Syrian Civil War War in Iraq (2013-2017) Yemeni Civil War (2014-present)[citation needed] Houthi–Saudi Arabian conflict Sudanese civil war (2023-present) |

| Production history | |

| Designer | KBM (Kolomna) |

| Variants | Type 65 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 85.3 kg (188 lbs) 71.7 kg (158 lbs) without wheels |

| Length | 1.85 m (6 ft) travel position |

| Barrel length | 1.66 m (5 ft 5 in) |

| Crew | 4 |

|

|

|

| Caliber | 82 mm (3.22 in) |

| Action | Single shot |

| Carriage | Two wheeled with integrated tripod |

| Elevation | -20/+35° |

| Traverse | 250° in each direction for 360 total. |

| Rate of fire | 5 to 7 rpm |

| Effective firing range | 400 m (437 yds) |

| Maximum firing range | 4,500 m (4,921 yds) |

| Feed system | Breech loaded |

| Sights | Optical (PBO-2) |

The weapon consists of a large barrel, with a PBO-2 sight mounted to the left. It is mounted on a small carriage, which has two large wheels, which can be removed. The carriage has an integrated tripod, from which the weapon is normally fired. A small wheel is fitted to the front of the barrel to prevent it touching the ground while being towed. It is normally towed by vehicle, although it can be towed by its four-man crew for short distances using the tow handle fitted to either side of the muzzle.

The tripod can be deployed in two positions providing either a good field of fire or a low silhouette. Rounds are inserted into the weapon through the breech, and percussion fired using a pistol grip to the right of the barrel. The PBO-2 optical sight has a 5.5x zoom direct fire sight, and a 2.5x zoom sight for indirect fire.

- BK-881 – HEAT-FS 3.87 kg. 0.46 kg of RDX. GK-2 PIBD fuze.

- BK-881M – HEAT-FS 4.11 kg. 0.54 kg of RDX. GK-2M PDIBD fuze. 240 mm versus RHA. Muzzle velocity 322 m/s.

- O-881A – HE-FRAG 3.90 kg. 0.46 kg of TNT/dinitronaphthalene. GK-2 fuze. Muzzle velocity 320 m/s. Indirect fire maximum range 4500 m.

- Type 65 (Chinese) – HEAT 3.5 kg. 356 mm versus RHA. Muzzle velocity 240 m/s.

- Type 65 (Chinese) – HE-FRAG 4.6 kg. Warhead contains approx 780 balls – lethal radius 20 m. Muzzle velocity 175 m/s. Max range 1750 m.

.mw-parser-output .div-col{margin-top:0.3em;column-width:30em}.mw-parser-output .div-col-small{font-size:90%}.mw-parser-output .div-col-rules{column-rule:1px solid #aaa}.mw-parser-output .div-col dl,.mw-parser-output .div-col ol,.mw-parser-output .div-col ul{margin-top:0}.mw-parser-output .div-col li,.mw-parser-output .div-col dd{page-break-inside:avoid;break-inside:avoid-column}

Afghanistan[12]

Afghanistan[12]

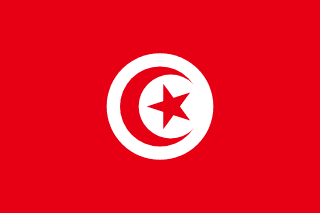

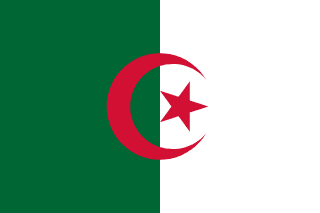

Algeria: 120 as of 2016[update][13]

Algeria: 120 as of 2016[update][13] Angola[11][14]

Angola[11][14] Bulgaria[11]

Bulgaria[11] Cambodia[11][15]

Cambodia[11][15] Chad[11]

Chad[11] China[9][16]

China[9][16] Egypt[11]

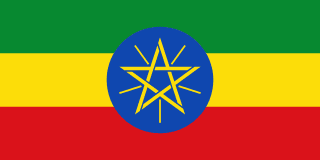

Egypt[11] Ethiopia[17]

Ethiopia[17] Guinea[11][18]

Guinea[11][18] Guinea-Bissau[11][19]

Guinea-Bissau[11][19] Iran[20]

Iran[20] Iraq[21]

Iraq[21] Libya[6]

Libya[6] Mozambique[11][22]

Mozambique[11][22] Myanmar: Copy producing as MA-14.[23][24]

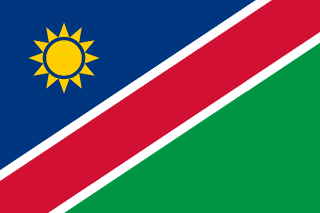

Myanmar: Copy producing as MA-14.[23][24] Namibia[25]

Namibia[25] Nicaragua[26]

Nicaragua[26] North Korea:[11] 1,700 as of 2016[update][27]

North Korea:[11] 1,700 as of 2016[update][27] Pakistan

Pakistan Palestine Liberation Organization[28]

Palestine Liberation Organization[28] Poland[11]

Poland[11] SADR[29]

SADR[29] Somalia[30]

Somalia[30] Sudan[31]

Sudan[31] Syria[11]

Syria[11]

Togo: Type 65 variant[11][33]

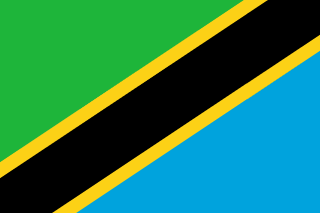

Togo: Type 65 variant[11][33] Vietnam:[11] B-10[1] and Type 65 variants[34]

Vietnam:[11] B-10[1] and Type 65 variants[34] Yemen[citation needed]

Yemen[citation needed]

Non-state users

Former operators

-

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit;word-wrap:break-word}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:”””””””‘””‘”}.mw-parser-output .citation:target{background-color:rgba(0,127,255,0.133)}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-free.id-lock-free a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/65/Lock-green.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-limited.id-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .id-lock-registration.id-lock-registration a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .id-lock-subscription.id-lock-subscription a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg”)right 0.1em center/9px no-repeat}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url(“//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg”)right 0.1em center/12px no-repeat}body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-free a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-limited a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-registration a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .id-lock-subscription a,body:not(.skin-timeless):not(.skin-minerva) .mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background-size:contain;padding:0 1em 0 0}.mw-parser-output .cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:none;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;color:var(–color-error,#d33)}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{color:var(–color-error,#d33)}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#085;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right{padding-right:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .citation .mw-selflink{font-weight:inherit}@media screen{.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{color:#18911f}}@media screen and (prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{color:#18911f}}Ezell, Edward Clinton (1988). Personal firepower. The Illustrated history of the Vietnam War 15. Bantam Books. pp. 142–144. ISBN 9780553345490. OCLC 1036801376.

-

David Campbell (2016). Israeli Soldier vs Syrian Soldier : Golan Heights 1967–73. Combat 18. illustrated by Johnny Shumate. Osprey Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 9781472813305. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

-

Neville, Leigh (19 Apr 2018). Technicals: Non-Standard Tactical Vehicles from the Great Toyota War to modern Special Forces. New Vanguard 257. Osprey Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 9781472822512. Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

-

Fitzsimmons, Scott (November 2012). “Executive Outcomes Defeats UNITA”. Mercenaries in Asymmetric Conflicts. Cambridge University Press. p. 217. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139208727.006. ISBN 9781107026919.

-

Neville 2018, p. 12.

-

Jenzen-Jones, N. R. (December 2015). “Recoilless Weapons” (PDF). Small Arms Survey Research Notes (55). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

-

Technically, only devices fired projectiles from a rifled barrel are called recoilless rifles, while smoothbore variants are called recoilless guns. This distinction is often lost, however, and both are often called recoilless rifles. From Julio, S. (April 1953), Las Armas Modernas de Infantería

-

“B-10 – Weaponsystems.net”. weaponsystems.net. Archived from the original on 2017-06-29. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

-

Shinn, David H.; Eisenman, Joshua (10 July 2012). China and Africa: A Century of Engagement. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812208009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2018 – via Google Books.

-

Jones, Richard D. Jane’s Infantry Weapons 2009/2010. Jane’s Information Group; 35 edition (January 27, 2009). ISBN 978-0-7106-2869-5.

-

Bhatia, Michael Vinai; Sedra, Mark (May 2008). Small Arms Survey (ed.). Afghanistan, Arms and Conflict: Armed Groups, Disarmament and Security in a Post-War Society. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-415-45308-0. Archived from the original on 2018-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 320.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 429.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 239.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 242.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 445.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 449.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 450.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 328.

-

Rottman, Gordon L. (1993). Armies of the Gulf War. Elite 45. Osprey Publishing. p. 49. ISBN 9781855322776.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 458.

-

Maung, Aung Myoe (2009). Building the Tatmadaw: Myanmar Armed Forces Since 1948. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 107. ISBN 978-981-230-848-1.

-

Gander, Terry J. (22 November 2000). “National inventories, Myanmar (Burma)”. Jane’s Infantry Weapons 2001-2002. p. 3112.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 459.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 406.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 265.

-

Zaloga, Steven J. (2003). Tank battles of the Mid-East Wars (2): The wars of 1973 to the present. Hong Kong: Concord Publications. p. 52. ISBN 962-361-613-9.

-

Salvador López de la Torre (20 November 1984). “El fracaso militar del Polisario: Smul Niran, una catástrofe de la guerrilla”. ABC (in Spanish): 32–33. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

-

Small Arms Survey (2012). “Surveying the Battlefield: Illicit Arms In Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia”. Small Arms Survey 2012: Moving Targets. Cambridge University Press. pp. 339, 342. ISBN 978-0-521-19714-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

-

“SPLA-N weapons and equipment, South Kordofan, December 2012” (PDF). HSBA Arms and Ammunition Tracing Desk. Small Arms Survey: 9. February 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-22. Retrieved 2019-01-02.

-

Worldwide Military Videos (14 April 2014). “Syrian Rebels Fire B10 Recoiless(sic) Rifle”. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19 – via YouTube.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 474.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 297.

-

Bender, Jeremy (17 Nov 2014). “As ISIS Continues To Gain Ground, Here’s What The Militants Have In Their Arsenal”. Business Insider. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

-

Small Arms Survey (2006). “Fuelling Fear: The Lord’s Resistance Army and Small Arms”. Small Arms Survey 2006: Unfinished Business. Oxford University Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-19-929848-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-30. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

-

Military Balance 2016, p. 492.

-

V. Hogg, Ian (1988). Jane’s infantry weapons 1988-89 (14th ed.). London: Jane’s Pub. Co. p. 405. ISBN 978-0710608574.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (February 2016). The Military Balance 2016. Vol. 116. Routlegde. ISBN 9781857438352.

- Artillery of the World, Christopher F. Foss, ISBN 0-7110-0505-2

- Brassey’s Infantry Weapons of the World, J.I.H. Owen, Loc number 74-20627

- (in Russian) A history of the B-10.

pcs.c1.Page.onBodyEnd();

Source: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-SA 4.0. Changes may have been made. See authors on source page history.

Eksplorasi konten lain dari Tinta Emas

Berlangganan untuk dapatkan pos terbaru lewat email.